Beauty and Knowingness in The Last Unicorn

It is a brilliant work, but does it meet this moment?

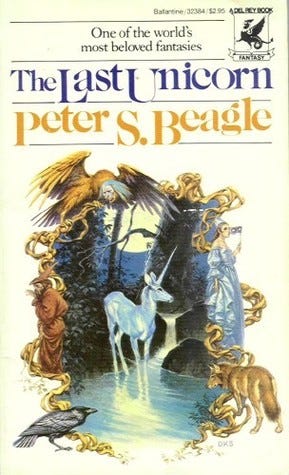

I recently reread The Last Unicorn by Peter S Beagle. At least, I thought I was rereading it. I thought I had read it in my youth. I remembered the title and the author’s name. I remembered that it was a beautiful and sad book. After 40 years, I did not remember anything specific about the plot, but I expected that it would all come flooding back to me after a few pages. It never did. Right to the end it seemed entirely new to me. Now I’m wondering if I ever did read it, or if I merely knew of it by reputation, and somehow the deceitful process of memory turned intent into completion over the years.

This is quite possible. It was not easy to lay hands on specific books in the 70s in a small town in Nova Scotia, particularly if one did not have money or a driver’s license for a trip to a Halifax bookstore. There was no Amazon and no Kindle. Tracking down books could be a quest in itself. Quite possibly, I heard of it and sought it but never found it, and what I remembered was wanting it rather than possessing it.

This thought is rather in the spirit of the book. It is full of whimsy about wanting and possessing. It is beautiful and sad, just as I remembered (or expected) it to be. And yet there is something about it that I found unsatisfying. It is something I think I would have found satisfying had I read it in my teens (as perhaps I did).

The thing that would have delighted me then, but spoils it for me now, is the constant play with language and the pervasive knowingness. The narrative is full of slyness about the fairytale form, even as it tells a fairytale. The characters are aware that they are living in a fairytale, they know the rules of fairytales, and they are not above reminding each other of them as the story develops. At one point, the protagonist, Schmendrick, says:

Haven’t you ever been in a fairy tale before? […] The hero has to make a prophecy come true, and the villain is the one who has to stop him—though in another kind of story, it’s more often the other way around. And a hero has to be in trouble from the moment of his birth, or he’s not a real hero. It’s a great relief to find out about Prince Lír. I’ve been waiting for this tale to turn up a leading man.

There is a lot of this sort of thing. The book romps around between fairytale and metafiction. Of its kind, it is brilliantly done, and it is a classic far beyond the need for my judgment of it. What I have to say here is not a review or a critique, but a consideration of my own reaction to it.

I have said many times that good novels create experiences. This is backed up by the neurological research on stories that shows that the same parts of the brain are involved in receiving stories as in receiving real experiences. Does it follow that a novelist should always seek total immersion in the story so that the reader feels like they are present in it, so that the telling disappears in the tale? If so, The Last Unicorn would be a bad book. Passages like the above are constantly pulling the reader out of immersion in the underlying story.

But it is not as simple as that. Immersion in the story, in what Tolkien called the subcreated world of the story, is certainly important. But the reader is also aware that they are reading a book. If the language of the book is a gateway to experience, the reader is also aware of the language itself. Even if the same neurons are firing as in real life, the nature of the experience produced by reading a story is different from that of having an adventure in the real world.

When you are reading, you have a kind of dual presence. You are in the experience of what is going on in the moment of the story, with all its grit and blood and love and fear. But you are also in the moment of reading, with all its comfort and indolence and love of language and capacity for contemplation. One can, and often does, lay a book down on a knee for a moment to pause and contemplate the pleasure and the beauty of it, or to absorb (or take a respite from) the glory or horror or pain or delight of the rough and gritty texture of the story experience itself.

This dual presence is fundamental to the nature of story. Our capacity for it is one of the most remarkable aspects of human nature. Our ability to be both engaged in furious action and calm contemplation at the same moment is astonishing, once we pause to think of it. But without it, there would be no literature. This dual presence is the only way that literature could work at all.

Every novelist, therefore, has to take account of both parts of the reader’s experience. But there is more than one way of going about this. One way is simply to tell the story and to leave it to the reader to decide how and when and why to put the book down on their knee and give themselves over to contemplation. The other is for the author to plunge the reader into the story at one moment and the next to pull them out again, wringing wet and gasping, and subject them to a chat, a lecture on their theory of bimetalism, a bit of mockery, or a few jokes.

The Last Unicorn is a book of this latter type. It demonstrates both the possibilities and the drawbacks of this form. And where once I think I would have relished the possibilities, now I find myself a little wearied and a little grieved by the drawbacks. One has the sense all the time that the author is playing with the reader, even laughing at them, creating emotions in them, and then mocking the very emotions he has evoked.

That takes extraordinary skill, of course. But we should be cautious when the principle thing we take from the experience of art is admiration for the skill of the artist. Such admiration may be well deserved, but to the extent that one has noticed the skill, one has been distracted from the art. Admiration for the skill of the artist should be part of the cooldown from the experience of art. It should not occur at the climax of the experience, but in the moments of contemplation and gratitude which follow the climax.

The Last Unicorn is beautiful and sad, but in a knowing, winking sort of way that mocks the emotions it evokes even as it evokes them. It almost seems to congratulate the reader on knowing the emotion and discounting it, even as they are having it. It gives the reader permission to be knowing and sentimental at the same time. It is quite the party trick. But I could wish for the sentiment straight up without the knowingness. The knowingness prevents any tear from falling, and I prefer books that make me weep.

Perhaps it could not be otherwise, at least not in our knowing times. Perhaps if the tale were told straight up it would be simply too sentimental to bear. Perhaps Beagle saw correctly that in order to tell a story as sad and sentimental as the one he had in mind, he would have to cut the sentiment with knowingness to keep the resulting dish palatable.

Or maybe it is quite the other way around and, like a painter seeking to make a patch of green stand out by placing a touch of red beside it, the knowingness is actually there to heighten the sentimental reaction of the reader to the events of the story itself.

The effect on me, though, is that I lose the sentimental emotion of the piece in having it pointed out to me. I remark on the technique. I admire the cleverness of the construction and the language, but I am out of the moment. The moment of contemplation comes not with a deepening of the emotion but with a diminution of it. I contemplate not the experience but the effects that produced it. The final reward of the book is not the sweet sadness of it, but knowingness that sees the sweet sadness of it and recognizes the artificiality of the emotion in oneself and, by extension, in other readers.

Perhaps the intention, and perhaps for many readers the effect, is just the opposite. By acknowledging their knowingness about fairytales and storytelling, it worms below the reader’s easy cynicism to present real sweet sadness, even for these so knowing characters and thus for the so knowing reader. If that was the intention, and if it does have that effect, then bravo to Peter Beagle for pulling it off. But it doesn’t quite work on me. At least, not anymore.

Maybe it is a tragedy that this doesn’t really work on me anymore. And if my pointing it out has made it not work on you anymore, then I apologize most abjectly for that. It is no good bargain to trade the delight in artifice for knowingness about the tricks of the artificer.

The source of my disquiet may simply be that I am growing sentimental as I age. It is a common enough development. Is it that, as I grow older, I have simply come to value cleverness less and sentiment more? The old are thought to be less clever and more sentimental than the young, though it is the young who think so. I prefer to think that my growing preference for sentiment over cleverness is a symptom of increasing wisdom. Except that I am as distrustful of sentiment as I am of cleverness, so perhaps wisdom is something else altogether.

There is something else that bothers me about The Last Unicorn. In her essay, “Haven’t you ever been in a fairy tale before?”: Peter S. Beagle’s The Last Unicorn, on Tor.com, Bridget McGovern says,

Somehow, after all the talk of myth and stories and what’s real and what’s not real, you feel somehow that in the end, you’ve been given something remarkably honest—a story that’s not about what’s true or not true, but one that accepts that there’s some truth scattered through almost everything, glinting beneath the deadly serious as well as the completely ridiculous, the patterns of literary conventions and the randomness of real life.

I think that is a reasonable analysis of the text, and that idea of fragments of truth everywhere is just the sort of conceit that appeals to the young mind. It is certainly the sort of thing that appealed to my young mind. And why shouldn’t it? Part of growing up is discovering that what you once accepted as undoubtable truth from parents and teachers is actually quite doubtable and sometimes manifestly wrong. The truths of childhood do indeed lie shattered everywhere, a condition that can lead either to pride or despair, depending on one's temperament and the times. (It seemed to tend more towards pride in my day. It seems to tend more towards despair today.)

But to encourage either attitude in the young mind now seems to me to be wantonly cruel and wrong. What we should be saying to them is this: truth is much harder work than you have been led to believe, but the worst thing you can do is grow cynical about it. (This is what universities used to tell students. Now they tell them the opposite.)

But perhaps it is unfair to lay this at Peter Beagle’s door. The universities of my day were not exactly paragons of reason, truth, and civility. (It could justly be said of Twitter that it brought academic incivility to the masses.) They were home to idealogues then as now, though there were idealogues of different stripes then, and a goodly number of men and women of reason as well. But even the idealogues had some respect for reason and rigor in those days and encouraged their students to listen seriously to other points of view and work hard to rationally defend their own ideas and rationally critique those they disagreed with.

Playing games with the idea of truth and reality seemed a lot less perilous then than it does now. Shaking people out of the self-assurance that they already have the whole of the truth is, after all, a necessary part of inculcating reason and scholarly rigor in a growing mind. It is not necessarily that the medicine is deadly as that the dosage has been badly misjudged. But, having overdosed as badly as we have, is the medicine still appropriate, even in a moderate dose?

In some sense, of course, the medicine is needed as badly as ever. The death of reason and rigorous scholarship has left many young people today in utter conviction of simple-minded ideologies and grossly misguided and sometimes outright fabricated views in the humanities, and increasingly in the sciences, that a shaking of their confidence in what they think they know would surely be salutary. But I don’t think its effect will be restorative without also something to inculcate a return to discipline and rigorous hard work in seeking a more objective view of reality.

So perhaps that is where my disquiet comes from. Not that The Last Unicorn is not good of its kind, even great of its kind, but that its kind does not seem the thing most needful in our particular moment. Or, at least, in my particular moment.

How about you? Are there books you read in youth (or thought you read) that seemed unfamiliar on re-reading, or that struck you differently at a different point in your life?

Do you feel the same way about The Last Unicorn?

And are there books, old or new, that you think are particularly needful in our present moment?

This is a brilliant review. I haven’t read the book, but the exploration of the appeal of cleverness over sentiment for the young is terrific. Here are some quotes I like, “[A]s I grow older, I have simply come to value cleverness less and sentiment more . . .. The old are thought to be less clever and more sentimental than the young, though it is the young who think so. I prefer to think that my growing preference for sentiment over cleverness is a symptom of increasing wisdom. Except that I am as distrustful of sentiment as I am of cleverness, so perhaps wisdom is something else altogether."

It's a remarkable novel, and its concerns about the differences between fantasies and reality are still relevant. Much of Beagle's oeuvre deals with this regardless of how long the story is- he is a fantasy writer constantly in negotiation with the rules of his game.