Normal, Wonderful, or Terrible

Why it is the Present, not the Past, that is Weird

With this essay I begin a new series called The Anomalous Now, which examines how the unique circumstances of today make the modern world unlike anything in our past. There is a strong tendency in contemporary historical fiction, and in journalism, politics, and other fields, to treat the past as a punching bag, and to see today as the enlightened nirvana to which all good people of the past naturally aspired. How could the people of the past believe such terrible things? How could they behave in such despicable ways? Clearly everything would have been better if they had all thought and acted like a modern person would.

But this is nonsense. The thoughts and actions of people in the past were a function of their circumstances, just as our thoughts and actions are a product of our circumstances. Our thoughts and actions seem so different from theirs not because we are better or smarter than them, but because our circumstances are so different from theirs.

The present is an anomaly. We only think it normal because we live in it and don’t know any better. But our failure to see the anomaly that is the present impairs our ability to read or understand history, or historical novels. Or, for that matter, to deal with politics and ideology generally.

As a novelist working largely in historical fiction, I read a lot of published historical fiction, but also, through workshops and critique groups, a lot that is unpublished, and in both I often find places where the author seems to have missed something about the past because they don’t know how anomalous the present is.

Most historical novelists do a lot of research to “get the details right”. But time and again I find that both the published and unpublished works get more than the details wrong. They get wrong what I will call, with clumsy coinage, the deep ground of history. The cake that holds up the icing.

The phrase “deep ground of history” may sound pompous. It may sound like I’m talking about a deep knowledge of history, in the sense of knowing a huge amount of historical facts, the kind of deep knowledge that only a full time historian could possess. But it is not really that at all. Rather, it is a matter of not being deceived by the many ways in which the present is an anomaly, unlike any age before it. In this series I plan to examine the various ways in which the present is an anomaly and how this anomaly can alter both our expectations and our judgements of the past.

So this is clear from the beginning, while I do have an MA in history and one year of a PhD program, I am not a scholar and have never worked as a professional historian. This is not about knowing more history. It is about recognizing how much, and, more importantly, in what ways, the present is an anomaly.

Missing the deep ground of history can make even the simple matter of getting the details right difficult. Thanks to the web, it is an easy enough matter to look up almost any detail you might need. If the web won’t give you the detail, it will give you the book that will. But writers who don’t know the deep ground of history may not realize when they need to look something up.

For example, I read a manuscript not long ago in which the writer had a stage coach spinning its wheels in the mud. Vehicles stuck in mud spin their wheels, right? We have all seen that. It is the sort of thing that will spill from your pen without thinking about it. Except that a stage coach, or any other horse-drawn vehicle can’t spin its wheels. Only a vehicle with an engine can spin its wheels, and then only the wheels to which power is applied. But the image of a vehicle stuck in mud spinning its wheels is so fixed in our modern consciousness that it is really not so remarkable that a modern writer might write that of a stage coach, never pausing to think of its implausibility. As someone who may or may not have been Mark Twain said,

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

Wheels capable of spinning themselves are an artefact of the age of portable mechanical power, a very recent development historically. The deep ground of history behind this is that the sources of mechanical power available to mankind over the centuries have been wind and moving water and animal muscle. Turning the energy released by fire into motion, which is a requirement for creating a wheel that spins itself, is one of the foundational anomalies of the present, and shapes many of the others. It is not a detail, but a deep systemic difference. It is so big that it is curiously easy to miss. Perhaps this is because it is so big it is hard to see the edges of it. Portable mechanical power is so pervasive in our age that it is difficult to imagine life without it.

But this deep technical difference is just one of the causes of what is the greatest anomaly about the present, which is its extraordinary wealth and the huge number of people who today are NOT living in extreme poverty.

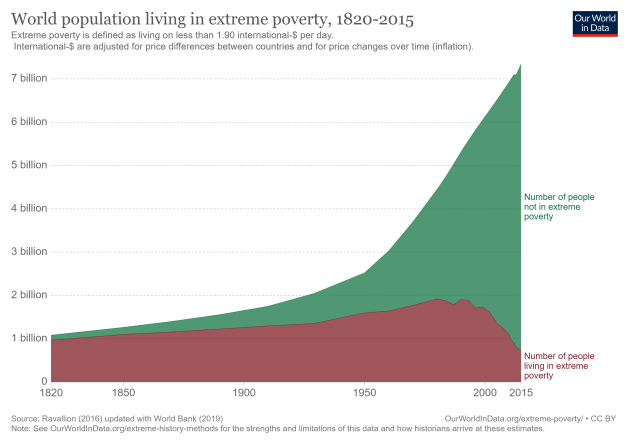

Since 1820 the population of the world has grown from one billion to seven billion, and yet the number of people living in extreme poverty has declined both in absolute terms, and in relative terms, with the steepest declines in poverty coming in just the last twenty five or so years.

Now, this chart has stirred up a lot of controversy, essentially between the apologists of capitalism and socialism, and you can get different curves by using different data sets and assumptions. (This is true of all attempts to visualize large and complex subjects.) But my interest in this is not to judge between capitalism or socialism. To me, this is about technology (considered broadly — better ships as well as better chips), and the virtual elimination of extreme poverty in technically advanced countries. Rates of poverty (not to mention the definition of poverty) and rates of literacy and infant mortality can only be estimated from incomplete data, but the delta between then and now is undeniably huge.

These technically advance countries are the countries where historical fiction is largely written and read, and where most of it is set. The writing and reading of novels is, in itself, a wealthy person’s occupation. The poor do not have the time or the resources for it, nor, generally speaking, the education. Their artistic expression tends more towards music and dance than literature.

But if extreme poverty and its consequences have largely been eliminated in the novel-reading countries, it was not so in those same countries before the industrial revolution, or indeed, until the effects of the industrial revolution had finally worked their way down to all ranks of their societies. I’m illustrating the point with charts for the world, because those are the ones I could easily find, and that are licensed for reuse. But they downplay, rather than exaggerate, the effects for the technically advanced countries today.

So, my point here has nothing to do with which economic system works best or exactly which data set is the right one to use. My point is simply that, in the developed world at least, there has been a vast growth and distribution of wealth and that that change creates an anomalous present in which the world and life in it looks very different from any time in the past. For example, this extraordinary increase in wealth coincides with extraordinary changes in living conditions:

In 1820, 88 percent of the world’s population could not read and 43% of children died before they reached five years old. That is staggering, and the 1820 numbers would likely be better than for the centuries that preceded them, since there had already been considerable economic and technical development by 1820. (For a fuller exploration of these numbers, see the article from which I borrowed the charts.) If you break it down by country and look at the developed countries you will see that the contrast are even more stark, as Hans Rosling shows in this video.

This video is a pretty good summation of the anomaly that the present has become.

Historical novels seldom deal with the poor, but the rich of the past were poor by our standards, and their children too regularly died before reaching adulthood. We would be scandalized today to find that anyone in a developed country lacked electricity and running water, but that was everyone in 1820. Everyone lacked vaccinations, antibiotics, and analgesics. No one owned a car, a fridge, a television, or a mobile phone. No one had internet service, and few had access to any quantity of books, even if they did know how to read. It you are ever offered the choice between living in a studio walkup in the poorer parts of Paris today or the palace of Versailles in the reign of the Sun King, choose the walkup. You will live longer and in a great deal more comfort.

Why does this matter for our appreciation of history and historical fiction? Essentially it comes down to one factor: expectations. We could reasonably say, I think, that our reactions to things fall into three categories: the normal, the wonderful, and the terrible. The normal is what you see around you every day. The wonderful are the good things that you rarely see. The terrible are the bad things that you rarely see. Normal, wonderful, and terrible are not constants. Wonderful and terrible are simply the extremes outside of whatever your experience tells you is normal.

For a family to loose a child to a simple fever at four years old is terrible today. In 1820, it was sad, of course, but it was normal. You had probably seen it happen several times to other people before it happened to you. It was not a terrible scandal as it would be today, it was a commonplace tragedy. You did not expect that the world should or could work any differently. This is why, in The Wistful and the Good, this is the very first thing I tell the reader about Edith at the beginning of Chapter 2:

Edith, Lady of Twyford, had never lost a child. She knew no other woman over thirty who could say the same thing. She had five daughters living and a sixth making her awkward and clumsy. But there are other ways to lose a child besides death.

Something that is ordinary to us — that our children should live — is something wonderful to Edith. This then sets up the fear of other kinds of loss which she fears and which she will experience as the book goes on.

The anomalous nature of the present has fundamentally changed what we regard as normal, wonderful, and terrible. Our values and our expectations have shifted accordingly. This affects almost everything we see in the past, and is the cause of almost everything we fail to see. A wheel spinning in the mud is normal today. It would have been miraculous in 1820.

What we regard as normal, wonderful, and terrible affects both what we think should be done, and what we think can be done. It changes whether we feel fortunate or unfortunate. It changes whether we see others as wise or foolish, as cruel, kind, or indifferent.

What makes the past such a difficult subject to approach, however, is not how weird and strange the past is, but how weird and strange the present is, how far it has shifted what we think of as normal and therefore what we think of as wonderful or terrible.

It is not at all an exaggeration to say that while there would be many differences between them, a man of AD 1700, AD 700, 700 BC and 1700 BC would understand each other’s way of life, opinions, loves, and loyalties far better than they would understand those of a man of 1970 or 2022. For one thing, it is a virtual certainty that the men of those past eras would all have been farmers, because that was the normal occupation of human beings for thousands of years.

Of course, we are not entirely unaware of how anomalous the present is. In some ways we boast of it. We think of the now as a time of reason, in contrast to the superstition and ignorance of the past; as a time of compassion in contrast to the cruelty of the past, as a time of progress as opposed to the stasis of the past. We think we have become better people, even as we pour scorn on those we think have callously and obdurately refused to come out of the darkness of the past and joined the new enlightened.

But curiously, these attitudes get the anomaly of the present exactly backwards. They complain about the past as if hearts were different when hearts are probably the one thing that are not different at all. Hearts are the same, but what is normal, wonderful, and terrible has changed radically, and that radically changes how people live out the promptings of their hearts. If we don’t understand how normal, wonderful, and terrible have changed, we are likely to misjudge the hearts of people of the past, and to be unjust to them.

In this series, I plan to explore how anomalous the present is and how the anomalies of the present warp our view of history, beginning with more practical things and working towards an exploration of attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

As I noted above, while I was trained in history, I am not an historian. I am a novelist, and my chief concern is the way the anomalies of the present affect the readers and writers of historical fiction. I am not a scholar and I have no intention of trying to bring the argument of this series up to scholarly standards, or to do the depth of research that would be needed to support its argument in a scholarly fashion. I would, though, welcome any insights or corrections that scholars might choose to offer.

Beautifully said, and so important for both writers and readers of historical fiction. I was trained in anthropology and archaeology (i'm not a scholar either ;-) and I've been disturbed by the trend in those fields, gaining momentum lately, of interpreting the past through the lens of the present and its preferences, experiences, and values. We seem increasingly unable--or unwilling--to understand the past on its own terms. The same happens in much of historical fiction. If the past is a foreign country, as I like to think of it, I don't visit to conquer, pass sentence, or impose my own culture, but for the opportunity of experiencing and learning about a culture different from my own. We can't understand or appreciate other cultures--past or present--when we're spellbound by our own.

Really interesting proposition (the wonderful, terrible especially). I’ll be interested to see what you do with it. Loved the Rosling video.