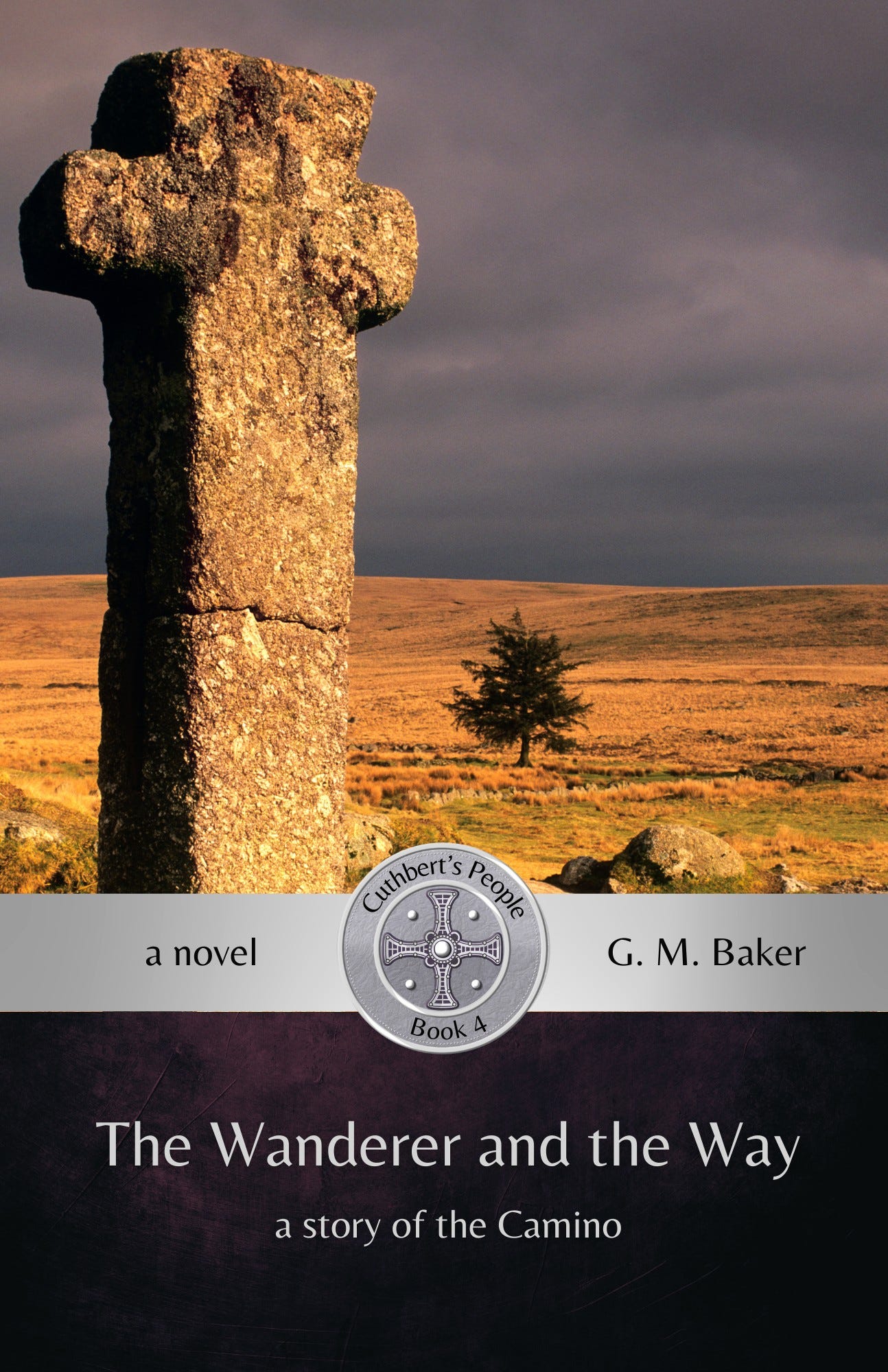

This is Chapter 20 of The Wanderer and the Way, now available for purchase.

Two pilgrims came walking down out of the Pyrenees, dirty, ragged, and terribly thin. One was a young man with a dented sword and a scarred cheek. The other was a young woman whose beauty could make men stop and catch their breath, for all that she was ragged and sunken cheeked, and the lissom curves that were native to her figure were all but lost to privation. They came to the door of a small convent that stood just outside the village of Imus Pyrenaeus where they knocked upon the door and were admitted and taken at once to the infirmary.

Theodemir and Agnes had grown very close on their journey through the Vascone country. At one point they had again encountered a pack train like the one before, this time coming upon it around a bend in the road so that there had been no opportunity to shield Agnes from their eyes. And whether it was true that any other woman would have been in as much peril or only one who looked as she did, the men of the pack train had taken one look at her and decided they must have her. Two of them had come at Theodemir with their knives while the third had grabbed Agnes and begun to drag her away. The two men had circled Theodemir. They were more lightly armed than he, having only their long knives against his sword and shield, so they darted in and out at him, each trying to make an opening for the other. He had been nervous at first, jumping at each lunge they made, but then he had seen the third with his grubby arms around Agnes, pulling her away towards the trees. He had rushed at one of his attackers then, and as the man had leapt away from his rush, he had tripped on a stone in the road and Theodemir, without a thought or stab of conscience, had driven his sword into the man’s belly. In the rush of the fight, though, he had forgotten what he had been told about retrieving his sword, to twist it to break the suction of the flesh upon the blade, and as he was tugging uselessly on the trapped weapon, the other man had been on his back, and he had only been saved from a knife in his back by the chance that the man’s blow had been miss-aimed and had struck the tough leather of Theodemir’s belt. It was a rolling, gouging, eye-poking, bitter fight then, from which Theodemir, in a blood rage, had emerged bloody but victorious. His two adversaries dead on the road, he looked around desperately for Agnes and heard her cries coming from the woods. Remembering what he had been taught, he then twisted the blade of his sword and pulled it from the first man’s body, and ran towards the cries. There he had found the third man sitting on a prostrate Agnes and battering her with his fists as she fought him. Theodemir had shouted no challenge. He had driven his sword into the man’s back. When the man still groaned and twitched after falling aside from Agnes, he had twisted out the blade and plunged it into the man’s eye socket. He had thrown all his weight upon the blade to drive it deep into the man’s brain, from which it then took some effort to retrieve the blade.

Agnes had been bloodied and badly bruised by his attack, but Theodemir had come in time to save her virginity. She had discovered in that bitter struggle that her life and her virginity were both things that she still cared to preserve and Theodemir, who had discovered in the fight a confidence that had never been in him before, had become her unquestioned protector, as capable and reliable in her eyes as Hathus had been.

He had held her while she wept and then had searched for the right plants to poultice her cuts. His own injuries were slight, a cut on his cheek that had bled freely at first but soon stopped of its own accord, a bruise where his belt had protected him from the second man’s blow, and some scrapes and bruises on his fists from his fight with the second man. It was only after their wounds had been tended and he had nursed and comforted Agnes through the first shock of the attack that he had realized that he should have been searching the pack train for things they could use and finding the fittest and most compliant mules for them to ride. But this thought was all in vain when it finally came to him, for by then the road was empty, the mules of the pack train, knowing their route well enough, and being uninterested in waiting for the men who were supposed to attend them, had trotted on down the road and disappeared.

He had decided that he would not risk human contact again until they were out of the land of the Vascones and could find refuge in a religious house in the country of the Franks. This had made for slow progress, for while Theodemir had not lost all of the toughness and strength of body that he had acquired on his long walk from Rome, Agnes, though she was uncomplaining, had been living a sedentary life in Iria Flavia. Her feet were soft and she tired easily, particularly in the first week after her near-rape by the Vascon, while her cuts and bruises healed. It was hard to find enough to eat on that journey, and while heat had been her undoing during the late summer on the Douro, in the early autumn of the Pyrenees, it was cold and wind and rain that oppressed them and sapped their strength.

On the first night after the attack, she had at first lain down apart from him, and he had lain wakeful, listening as she tried to control her weeping. Then she had come and lain down against his back and had fallen asleep there, while he had suffered through the night from every twitch and cry she made in her troubled sleep. She had done the same on each night that followed, which had become both a delight and a torture to him, though he would not for worlds have broken the absolute trust that she now showed in him. Her sleep became less troubled as the days passed, but still she could not bear to be parted from him, her sole guard and protector.

When they walked, they generally went in silence unless some question of the route or of the other practical difficulties of the journey required discussion. Around their campfire in the evenings, though, when they could find the wood and thought themselves safe enough to build a fire, she would tell him stories of her home and those she loved. She spoke of her beloved, indulgent father, Attor; her clever, ambitious mother, Edith, who had been born a slave but made herself up to lady of the manor by seducing the son of the estate; of her sulky sister Hilda, who she described with great admiration as the finest needlewoman in Northumbria; of chatty Moira; of the silent ever-running Whitney; of baby Daisy; and of another sister whom she had never seen, but whom her mother had been carrying at the time of her departure. She talked of her beloved Grandmother, Hunith, still a slave, and of Maida and various other relatives of her mother’s, all slaves still. She talked sometimes, though wistfully and guardedly, of Drefan of Bamburgh, the man she had been supposed to marry, and of Leif, the cousin of Eric, to whom she had offered herself, in violation of her promise to Drefan, the sin which, in her mind, was the cause of all the deaths that weighed upon her conscience. This, he understood, was her way of telling him that she now trusted him and would lie beside him at night to share the warmth of their bodies and to take comfort from his nearness, yet she would never take him to husband, lest this same curse should fall on him. She told him of Mother Wynflaed of Whitby, who had been a second mother to her, and of Sister Eormenburg, whom she seemed to regard as a rather strict but beloved grandmother, and of Eardwulf, the King of Northumbria, with whom, he perceived, she was still deeply in love, a perception that plunged him into even greater gloom than her refusal to marry him because of her curse. The curse, he believed, was imagined, and she might one day be dissuaded from her belief in it. The love for Eardwulf, though, was evidently real and, despite so many years apart, seemed fixed. She spoke of all the joys and discoveries of the twelve days of Christmas of the year of grace 793 in which Eardwulf had courted her, and of the sites he had shown her, and of his companions and their wives, for whom she held a deep affection. She spoke also of a week that she had spent alone in a hermitage on the high cold moors above Whitby, and of the angels and demons who had visited her there, and of how hard it had been to perceive which voices were of the angels and which of the demons.[1] It was only of Eric and of the life she had led since he had taken her from Whitby that she seemed disinclined to speak, almost as if it had been a dead time, a time of waiting, in which nothing worthy of memory had occurred.

She coaxed out of him stories of his mother, of who he had no real memory, she having died in giving birth to a sister who had died also, and who, between them, had killed the heart and spirit of his father, and made him a subject and supplicant of his elder brother, Witteric. A fever had taken his father just as Theodemir was coming to young manhood, but Theodemir believed, and Agnes confirmed him in the belief, that his father had really died of a broken heart. Of his life with Witteric after his father’s death, his unsatisfying years as a scholar in Rome, and of his long and weary trek back to Iria Flavia, he had little appetite for speaking. Of Lalla and Rosalina he was ashamed to say anything at all. Nothing in his career to date, it seemed, did him much credit, neither for accomplishments nor yet for affections given or won. He spoke more than once of his vision in the church in which God had commended Agnes to his care, and to his continued puzzlement as to what final service he was to perform for her. The first time, she listened to this tale with sympathy but some embarrassment. The second time, she seemed discomforted by it and asked him not to speak of it again. He had protested that it made no sense for her to believe herself cursed by God when God had so clearly made her the entirety of Theodemir’s vocation. But she had dismissed this in a way that made him understand that it was the conviction of her curse that made her discount his vision, as it made her discount his profession of love and his offer of marriage. And so he had learned that if he said no more about it, they could be friends, and a friend was all that she would consent to be. And so as friends they had continued, though she had slept pressed against his back each night for warmth.

And so, at last, they had come down out of the Pyrenees and, feeling themselves safer among the Franks and unable, in any case, to go much further or keep themselves alive without some form of human aid, had spied the village at the foot of the pass and the small convent it contained, and had gone there and knocked on the door. They had been admitted, generously fed, and allowed to wash. They had then been inspected by the infirmarian of the community who declared that privation was their only great ill and that rest and kindness and plenty were the only specifics required for their recovery. They had then been put to bed in the guest house on comfortable mattresses with clean sheets, which would have been, to Theodemir, the greatest of luxuries, except for the desolating fact that for the first time in many days, Agnes was not curled against him, lending her warmth to his body. Was she feeling the same sense of desolation, he wondered, or was she rejoicing to be at last relieved of the necessity of lying so? But he had not long for this doleful speculation, for he was weary to his bones, and sleep swiftly overtook him.

[1] See, St. Agnes and the Selkie.

Can’t wait to find out what happens next? The Wanderer and the Way is now available for purchase: https://books2read.com/thewandererandtheway

Comments welcome. If you spot a mistake, please let me know by replying to this email or by sending an email to author@gmbaker.net. Thanks!