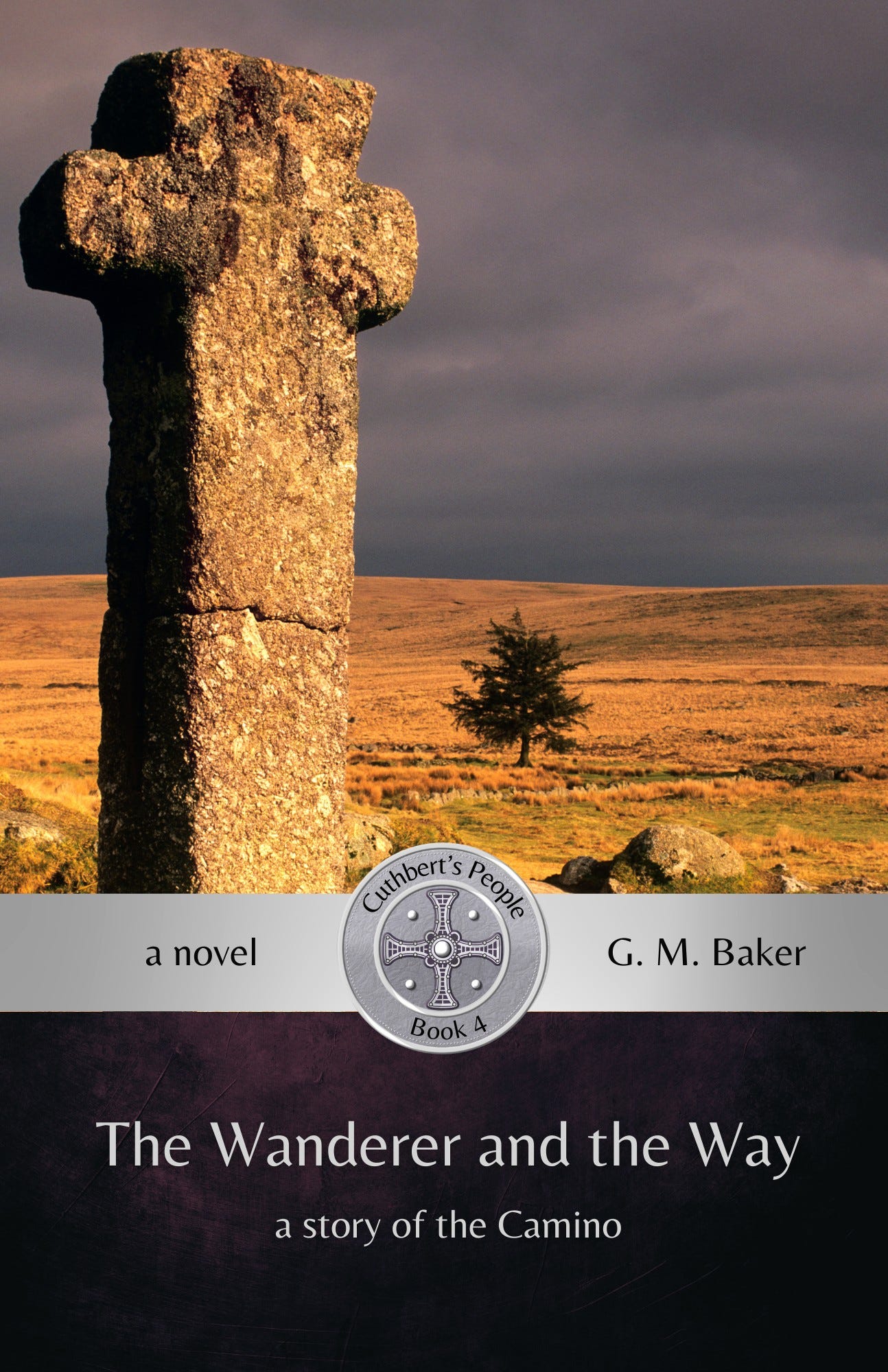

This is Chapter 22 of The Wanderer and the Way, now available for purchase.

Despite Mother Rotlenda’s urging, Theodemir did not immediately take his leave. Only certain parts of the convent’s grounds were open to men, and Agnes had been taken to the women’s side of the place and had remained there. Indeed, he suspected that she was being confined there, though his suspicions on this score were not sufficient to justify a violent entry into the women’s preserve to discover her. In any case, he was certain that she would require several more days of convalescence than he before she was well enough to travel, and he was in no mind to depart without speaking to her again. They had become close confidants through the hardest parts of their journey, and though he was conscious that this closeness had been born of her fear and her utter dependence on him, yet, he told himself, all human relationships were born of the specific circumstances and trials of life, and it was not to be thought that bonds forged in trial were not thereby sound and durable bonds. Indeed, the world not only understood but celebrated the bonds between men that are forged in battle so that a man will never in life forget or abandon the man he has stood beside in a hard fight. And a hard fight they had had of it, Agnes and he, and a bond they had forged as they traveled, and surely such a bond would not simply melt away like the snows on the mountain tops before the morning sun.

But then again, he reminded himself, the bonds that bind men and women together are not of the same character as those that bind men to men. And though he and Agnes had lain together as close an any married couple in their bed, yet the essential element of the marital bond had been absent. Indeed, the closeness of their sleeping arrangement had existed only because she had trusted implicitly that the essential element should neither be contemplated nor attempted. It seemed strange and wonderful to him that he, who had never been able to keep the custody of his eyes towards her beauty, had been able to keep custody of every vital part of him towards her physical presence against his body. But then he had known, with a certainty in his soul, that she came to him as one narrowly saved from rape and that therefore any attempt at marital intimacy would have been the cruelest of betrayals since it would not only have recalled all the terror of that moment to her mind, but also deprived her of the last person in the world she trusted and had recourse to. That had been the nature of the bond they formed, a bond neither like the bonds of men to men nor of bonds of men to women, a bond that had arisen only because of Agnes’s desperate need for a protector and the accident of his being the only person available to provide that protection. Was this not indeed a bond that would melt like snow before the morning sun as soon as a more congenial protector became available, as it had now in the person of Mother Rotlenda?

Of one thing he was certain. If Hathus and his men, or indeed, Hathus alone, and perhaps any one of his men singly, had survived their encounter with the Moorish raiders, it would have been to them, not to himself, that Agnes would have looked for protection. She had chosen him only because he had been the last man in the world she could turn to.

He spent his days wandering about the district of Imus Pyrenaeus. There were men of the village who offered him friendship, drink, and conversation, but he was not of a mind to speak to anyone of Agnes nor yet of Hathus and the men whose company he had fled as they were about to go into battle. He well understood that his ambassadorship, undertaken in the service of his King, demanded this departure from the soldier’s path of honor. But it was not a distinction that he expected would commend him to ordinary men, particularly men who lived so close upon the marches of the Pyrenees and must therefore have had to stand shields-together against the many races of those mountains. To avoid the need for such conversations, he took to wandering around the old Roman camp that had once guarded the pass through which he and Agnes had descended out of the mountains. It had long since ceased to be of use. The baths were dry, and the watercourses broken and choked with weeds. The walls in several places had been torn down, and he had noticed pieces of the cut stone used to repair roads and build chimneys throughout the village, including in the convent.

Another favorite place for his ramblings was the stream called Laurhibar, which watered the village. It was a small and rather shallow stream, easily fordable, shaded by graceful trees and alive with small fish and skimming water boatmen. The yellow-brown woods around it were full of the gentle sounds of birds and insects about their proper commerce and society, and it seemed to him, as he paused and listened to it and watched the light play on the water, that he had stumbled into another kingdom, a kingdom of air and water where marriages were made and wars fought and daily bread was striven for and won, or sometimes lost, all unnoticed by men whose proper vocations occupied their time and their attention while he, for want of sure direction, wandered aimlessly.

On one of his rambles beside this stream, he came upon a white willow bending over the water. It was both a smaller tree and a smaller river, but it put him in mind so strongly of Agnes’s customary refuge from the heat of the day that he was irresistibly drawn to it. Sitting with his back against its trunk, looking out over the dappled waters of the Laurhibar, he felt a strong bond of communion with her, though she still remained convalescing behind the walls of the convent.

Beneath that tree he often found himself ruminating on the words that Mother Rotlenda had spoken to him. What she had said regarding Agnes’s belief that she was cursed by God and that any man to whom she made a promise was therefore doomed to die seemed to him a sober and obvious truth. Indeed, he had never believed in this curse. Agnes was, after all, God’s most perfect creation, and it made no sense that having made a woman of such perfection, that he should then curse her and forbid her ever from marrying. Why create a second Eve and then forbid her from ever knowing another Adam? But no sooner had this thought formed itself in his mind than he had heard a voice in his head that argued that God had indeed made a woman of a perfection beyond that of both Eve and Agnes and had indeed prevented that most perfect of her sex from ever joining with a husband in a marriage bed, God himself being her only and perfect spouse. And he had further subjected her to the horror of seeing her only son put to death on a cross. Even the fairest and most perfect of mortals was not preserved from agony. Perhaps, indeed, they knew it more than any.

And then another voice entered his mind—perhaps it was the voice of Mother Rotlenda. It scolded his first interlocutor, saying that it was ridiculous and bordering on the blasphemous to compare the blessed virgin mother to Agnes, whose only approach to perfection lay in her face and form and who was, in fact, a confessed sinner. At his point, he concluded that he was no more a skilled theological disputant in his own mind than he had proved to be among his tutors and fellow students in Rome.

This unhappy thought, in turn, brought him to what she had said about his vocation to Agnes. If he was as unskilled as he seemed in theological disputation, did it not follow that he should be equally unskilled in the discerning of spirits, which was, if he remembered St. Paul correctly, a gift given to some for the good of all, not to each person individually for their own benefit? He had fallen in love with Agnes. He had been enchanted by Agnes’s voice singing the psalms. His head and his heart had been full of Agnes as he had stood in the Church of Santa Maria of Iria Flavia, Bishop Quendulf droning on at his side about a quest that in no way spoke to his heart, for his heart had, at that moment, been wholly given to Agnes. Could it be then, as Mother Rotlenda had said, that it had not been the voice of God, but the voice of his own heart—let it be his heart at least, and not his loins, as Mother Rotlenda had suggested—which had conjured up his vision of Agnes in the church. And had not Agnes herself spoken with such weariness of the way so many men seemed to fall so easily in love with her. Could it be that he was indeed just another one of the bees drawn to the nectar of her bloom, their droning chorus driving both Agnes and themselves to madness?

Let it be so, then, he said to himself. Let it be so. But if it is so, if she is not cursed, and I am no more than a fool in love, why should we not marry? If I was at first a fool like all the rest, have I not proven myself more faithful and more restrained than any other suitor? And she was correct when she said that if we were married, my mad love would become a sane and proper love and that that love would be returned to me over the cradle of our firstborn child. What objection could there be to that from God, from Alphonso the Chaste, or even from Mother Rotlenda?

It was while he was sitting beneath this tree, lost in this hopeful speculation, that he heard a rustling in the branches as someone entered his sanctuary. He looked around and saw that it was Agnes. His heart stopped a moment, for the conjunction of the Agnes of his speculation and the appearance of the Agnes of the flesh for a moment seemed like another vision. Or perhaps it was the second and concluding part of the first vision and the exact and perfect consummation of his vocation.

“I escaped,” she said.

If before she had seemed like perfection in agony, she now appeared as perfection in relief. There was color in her cheeks and the terrible thinness had left her limbs, though she was still far from the plumpness that he imagined was native to her figure but which she had never possessed in his time of knowing her. But above all this was the smile with which she regarded him, for it was a smile such as he had never had from her before, even through the days of their privation and intimacy. She was genuinely pleased to see him on a day and in a place where she was free of all danger and want, something that had never been true of her in any moment of their acquaintance. It was as near to an ordinary moment between a young man and a young woman as had ever occurred between them and she had greeted it with a smile. And oh, what a wonder of love and hope and beauty was her smile!

“Escaped, Lady?” he said. “I wondered if they were holding you captive or if it was your choice to remain behind their walls.”

“I don’t think it is quite fair to say I was a captive,” she replied. “The gates are locked from the inside. But they did not want to leave me alone, and they certainly did not want me to see you. They stole my shoes, and I had to steal this dress just to have something to wear outside.”

Indeed, the dress she was wearing was far too voluminous for her slight figure, and she had a great swath of it tied up around her waist to prevent the hem from dragging on the ground. Her feet were bare.

“You sought me out?” he asked.

“Not really,” she said. “I just needed desperately to get out and go for a walk, so I found the stream and followed it. That’s how I found you.”

She came and sat down beside him. There was a lightness of spirit in her that he had never seen before. He did not dare to believe that all that had oppressed her had vanished, but on this day, in this moment at least, her burdens seemed forgotten, and he rejoiced to see it.

And then, to his astonishment, she placed her hand in his.

Can’t wait to find out what happens next? The Wanderer and the Way is now available for purchase: https://books2read.com/thewandererandtheway

Comments welcome. If you spot a mistake, please let me know by replying to this email or by sending an email to author@gmbaker.net. Thanks!