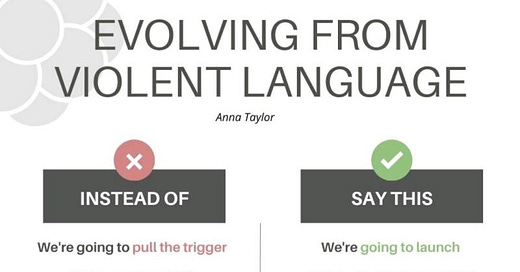

I stumbled upon this piece of silliness on LinkedIn, the home of much earnest Internet silliness. (Even the Guardian, which never met a bleeding heart it would not spatter across its pages, thinks this one goes overboard.) I could riff a little on whether “bad idea” should count as violent language (isn’t this “bad” as in apple, not “bad” as in intentions?) or just how silly “feed two birds with one scone” is. But I want to point out something else, something that goes beyond this individual piece of silliness. And that is the war on metaphor.

Because if we compare the phrases on the left with their suggested alternatives on the right, we see that in almost every case, they replace a metaphor with a bland literalism.

This is not entirely the case because very little of our language is truly metaphor free. “Launch” is as much a metaphor as “pull the trigger,” and “first pass” is plausibly a reference to jousting. But even among metaphors, there are those that have decayed into virtual literalism, meaning that they evoke no image in the mind beyond their dictionary definition. Such is the fate of the overused image, and you could argue that many of the so-called “violent” examples on the left don’t really evoke a violent physical image in the mind either.

But if many of them do not bring violent action into the mind’s eye, in every case they are nearer to doing so. And what is often missed is that metaphorical language is not less precise than literal language. On the contrary, it is almost always more precise and almost always creates a sharper and more memorable image in the mind.

Take the first example. This is a case of metaphor against metaphor. “Pull the trigger” calls a very specific image to mind: a finger pulling a trigger. And this brings with it everything that follows from that action: the crack of the exploding powder, the sickening flight of the bullet, the injury the bullet causes to whatever it hits. “Launch” may or may not call to mind the image of a ship sliding into the water, but even if it does, it is a less piquant image. Why? First because the word “launch” has at least partially decayed into literalism. And because pulling a trigger calls to mind an action of momentous consequence. Pulling a trigger, exactly because of its implicit violence, speaks to the weight of the decision to act.

“Jump the gun” isn’t a violent image at all. It’s a sports reference. To jump the gun is to start a race before the starter’s pistol is fired. No violence is being done by a starter’s pistol; it is just being used to make a sharp loud noise so that all the runners start at the same time. But what the phrase does is call to mind the tension inherent in the start of any race. It reminds us of how nervous, how keyed up, how anxious the runners are, and of the kind of emotional failure that is involved in letting that tension trick you into bursting from the blocks before the signal has been given. All of these implications are missing in the bland “start too soon.” “Jump the gun,” in other words, invokes a story. “Start too soon” does not.

“Let’s just roll with the punches” is a boxing metaphor for which “Let’s just move forward” is a complete mistranslation. Rolling with the punches isn’t about moving forward; it’s about avoiding the force of the blow aimed at you. Rolling with the punches allows you to keep your head on your shoulders. Having successfully evaded the attack may put you in a position to then move forward, but in itself it is a defensive posture. As a metaphor, the phrase speaks powerfully to anyone who is facing setback after setback in life. It is a metaphor that can give someone the courage to weather the storm, as well as the practical advice to move so as not to take the full force of the blow directly, be that blow literal or figurative. It is a hard idea to put across succinctly in literal language, which is doubtless why the author of this silly list got it wrong. But it also illustrates again that metaphorical language provokes sharper and more accurate thinking while literalism tends towards imprecision and vague thought.

To “take a shot in the dark” similarly speaks far more eloquently to the risks involved than the bland “take a guess.” Taking a shot in the dark is an act with potential consequences that should be considered carefully. Taking a guess is just lazy thinking. Why would one take a shot in the dark? Because it is the nature of the human condition that we can never act with perfect information. This is why it takes courage to act. You can never be sure of the consequences. Sometimes it is necessary to take a shot in the dark because the shot is important and the darkness cannot be lifted before it is too late to act. Such occasions cannot be avoided in life, but it is well that we should use a sharp and even violent metaphor to remind us what the consequences could be. The bland “take a guess” makes no such warning.

You have to reach pretty far to consider “blown away by his presentation” or “kicking an idea around” to be violent language. Blown away is more a reference to strong wind than to explosives, and “kicking around” is a sports metaphor with particular reference to soccer. But again, notice how much more vivid and forceful these terms are compared to their bland alternatives, “impressed by” and “thinking through.” Not to mention that kicking around is a group metaphor, so kicking an idea around means discussing it with other people as opposed to thinking it through by yourself.

The final example is another case of misinterpretation. A “straight shooter” is someone who hits the target. The implication is one of accuracy and truthfulness. Someone who is “pretty direct” is someone who spares no one’s feelings. Such a person may be both inaccurate and untruthful. Again the metaphor is more forthright than its mealy-mouthed alternative.

Still, you may ask, if metaphorical language is more direct and evocative, does that mean we have to use such violent metaphors? Couldn’t there be other metaphors that are just as vivid without being violent?

The answer to this is both yes and no. Yes in the sense that there are many vivid metaphors that are not violent, including several of those on this list, which are violent only in the fevered imagination of the person who compiled it. But many of our metaphors are violent, and appropriately so. Here’s why:

The key virtue of a metaphor is that it has a double effect. A metaphor evokes a story, and stories have emotions attached to them. The metaphor expresses not only the action but the emotions attached to the action. Thus, “shot in the dark” speaks not only to acting without complete knowledge but to the potential consequences of doing so. This evokes the emotions that attend that uncertainty. And this is important, because it is emotions that prompt us to act. When asked if we want to take a shot in the dark, we are reminded of the potential consequences of taking action. A certain chill is introduced by the emotions and practical overtones of “taking a shot,” and those emotions cause us to pause and think if this is what we really want to do. In this case, the use of violent language may forestall the taking of potentially violent action.

In storytelling, we need ways to express the inner state of characters. Since our inner states are not visible, we read each other’s emotions only through their actions and expressions. But our actions and expressions don’t always express the fullness of our emotions. Part of learning to live together with other people is learning not to express the full range of our emotions in public, which is why we don’t all act like three-year-olds when we are disappointed.

But the storyteller needs to get at those unexpressed emotions. They need to take the inner life and make it external so that it can be seen and known. They need to give faces to our fears, our hopes, and our emotions. In the written word, we have the option of stating the emotion clinically, and this is sometimes justified in the name of moving the story along. But it is also the dreaded “telling.” In order to “show” the inner state, we need to express it in external action. And such action must clearly be exceptional. It reveals nothing hidden to have your characters perform actions that they would normally do anyway. Therefore, the action that reveals the inner state must violate the norms to which the character would normally adhere. They must, in other words, be violent.

Thus in the movies and on TV, we regularly see characters sweeping everything off a desk in frustration, or smashing their fist or their forehead into mirrors. People do not do these things in real life. (Have you? Have you ever seen anyone else do them?) It is true that movies and TV often use violence gratuitously, in the service of creating a spectacle rather than as a means of storytelling, but in many cases, whether in books or on video, violent action is a necessary means of giving a face to the inner life.

This is true not only in small things and individual incidents. It can also be writ large across the whole landscape of a story. Whole plots express inner states through external action. Wanderlust is expressed through wandering. Jealousy is expressed through adultery. Anger is expressed through violence.

All of this is the work of metaphor. Some metaphors work at the level of words and sentences. Some work across the whole breadth of a story. But be they large or small, metaphors must stand out from the mundane statement of literal properties and actions. They must violate the norms of sight and sound and action for them to be perceived as metaphors at all. And they must be specific and vivid. They must catch the eye and the ear, and they must catch in the throat. They must have the dual effect of not only specifying more vividly than mere literalism can, but also evoke the emotions that attend the things they describe.

A soft, safe language is one devoid of metaphor. A language devoid of metaphor is a language devoid of the capacity for precision, for emotion, and for the expression of inner states.

This may not be an unintended consequence for the people who push this kind of linguistic Bowdlerism. It may, indeed, be the whole point. Under the guise of niceness and gentleness, the real point may precisely be to rob the language of its capacity for liveliness and precision. Propaganda thrives in an atmosphere of abstraction. It seeks to divorce words from the reality they are supposed to describe, thus keeping the listener from noticing the disparity between reality and the ideas being propagated.

Metaphors, far from taking us away from the real, work to keep language grounded in the real. The war on metaphor is no accidental thing. It is deliberate, and it is dangerous, and we should fight it to our last breath. That may or may not be a metaphor.

Nailed it!

I find it almost impossible to not see the original post as a joke or parody. Has it been confirmed that the author of the source wasn't simply trolling people who are sensitive to this kind of thing?