The Power of Difference in Drama

In story, men and women are different in kind, and this is essential to drama

Drama thrives on difference. The difference between rich and poor. The difference between David and Goliath. The difference between lord and peasant. The difference between man and woman.

Ah! There’s the rub.

And yet, of all the differences that drive drama, does any drive it farther and faster than the difference between man and woman, between Romeo and Juliette, between Lizzy and D’Arcy, between Gatsby and Daisy?

This is not a difference we like to talk about these days. Men and women, we are told, are not so different after all. It was only a cultural prejudice that made them seem so. Hollywood has set out to prove this point by making a bunch of distaff versions of traditionally male-led stories. The results, to be charitable, have been mixed. But I am not here today to argue that point. Rather, I want to take a step back and examine why the difference between men and women matters to drama, regardless of whether the difference in real life is large or small.

The occasion of this essay is a discussion in the Catholic Writers Guild forum about whether the Hero’s Journey model of story is exclusively male or whether the ladies get to play too. This discussion was triggered by a video that argued that Hero’s Journey was a male-only trope. I’m not going to link to the video because it is badly produced and is based on a complete misunderstanding of the Hero’s Journey model. It was merely the catalyst for the discussion which was in turn the catalyst for this essay.

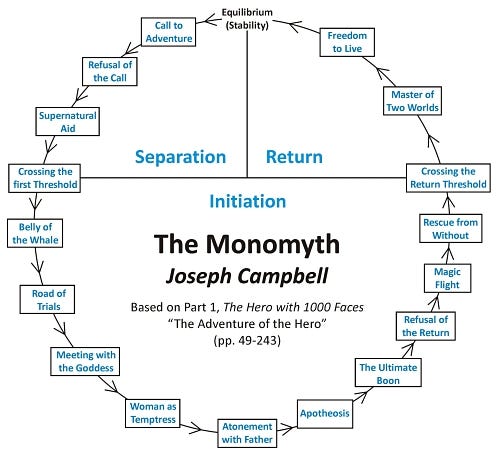

It is not the main point of this essay, but the video author’s misunderstanding of the Hero’s Journey model is worth talking about briefly. The video author claimed that the Hero’s Journey model was this: the knight goes on a journey, kills the dragon, and gets the girl. But that is not the Hero’s Journey. It bears a superficial resemblance to part of it, but it entirely misses the point. For the full story, read Campbell or Vogler, but Wikipedia has a reasonable summary of it. The essential point of it is that while the hero acts as an individual, they act on behalf of a community.

The full hero’s journey is not simply a voyage of acquisition but a journey of moral development, with three essential components: the departure, the initiation, and the return. It is in the return phase that the triumphant hero goes back to the community, bearing the treasure he has won for their benefit. But the return is not simple. Just as the departure and initiation phases of the journey require profound moral development, so too does the return. As the departure begins with an initial refusal to leave, leading to a crossing of the threshold into the other world, so the return involves a refusal to return followed by crossing the threshold back into the normal world.1

But, you may ask, as some in the discussion did ask, can’t a woman do all that, too? And the answer is that, at the physical level, she can. She may not march as far in a day or wield so heavy a sword, but she can still perform all the steps. So why can’t she follow the hero’s journey just as well as a man?

We enter here into a question of difference. Difference is the heart of drama. But what kinds of differences matter here? On the simplest level, there are differences of size and strength. You can certainly build a story on this difference. The classical example is David and Goliath. Both are men. The difference is simply that Goliath is bigger and stronger than David, and David is cleverer than Goliath.

But there are other kinds of differences. There are differences in kind. A man is different in kind from a stone. To a lesser degree, he is different in kind to a tree. To a lesser degree still, he is different in kind to a horse. And to a still smaller degree, he is different in kind to a woman.

That a man is different in kind to a woman is not in itself controversial. She can conceive a child, carry it to term, and feed it from her own body. He can do none of those things. But does their difference in kind go any deeper than that?

In the Catholic Church, only men can be priests. This is based on a difference in kind. Women could say all the things priests can say and do all the physical things that a priest can do. Nonetheless, the church regards them as more fundamentally different in kind from men, and this difference in kind means that men can be priests and women cannot.

I raise this not to argue for or against it but simply to point out that it is possible to believe that differences in kind can be thought of as something deeper than mere differences in the ability to perform physical actions. My concern here is with drama and with how difference drives drama. And since the difference between men and women is one of the principal drivers of drama, this difference of kind matters in drama because the greater the difference, the greater the potential for drama.

So, let us consider the nature of the difference in kind between men and women in the context of drama. The most compelling statement of this difference in the discussion came from Lindsey Bruno of Catholic Stories for Children. The difference, she suggested, is that the man slays the dragon while the woman tames the dragon.

Without any prejudice to the status of men and women in the real world, this strikes me as a profound truth about the roles of men and women in stories.

I’ve never been a fan of the tame-the-dragon trope, regarding it as the destruction of a core symbol of Western culture. But in light of Bruno’s point, I started to think about the taming of the dragon in literature and realized that all the examples I could think of were written by women. I can trace taming the dragon back to Edith Nesbit's The Last Dragon. How to Train Your Dragon is by Cressida Cowell. I haven't read Ann McAfree's work other than the titles, but presumably the people of Pern are taming the dragons they ride. In A Wizard of Earthsea, Ursula Le Guin has Ged tame a dragon by naming him. And then there's Vern, the private eye dragon of Karina Fabian’s series.

Tolkien, on the other hand, slays Smaug, and Lewis, in a sense, slays the dragon in Voyage of the Dawn Treader.

I am no master of dragon lore, and I am sure there must be counterexamples. If one among you is a great student of dragon stories, I would love to know if this pattern maintains across the literature. I’d also be interested to know if there has been any change in the distribution over the years.

However, Bruno pointed out that the woman taming the dragon is but one strand of a wider feminine trope, beauty and the beast, which brings works like Pride and Prejudice and Jane Eyre into the pattern. And it seems to me that this is how the feminine enters into the Hero’s Journey trope. Having slain the dragon, the hero becomes the dragon. He has become king and master of the wild lands. And being so, he is not fit to return to his old life in the village. To complete the cycle and return with the treasure, he must be tamed. And so, as Bruno again pointed out, by taming the hero, the woman allows for the child to be conceived and nurtured, thus allowing the cycle to continue.

Yes, some might say, but why can’t the roles be reversed? Why can’t the woman hear the call to adventure, cross the threshold, get the sword, slay the dragon, become the dragon, take the treasure, return to the village, and be tamed by the man?

And indeed, the trope of the man taming the woman is ancient. Shakespeare wrote it in Much Ado About Nothing and The Taming of the Shrew. I have written it twice myself in The Needle of Avocation and The Wrecker’s Daughter. So does that license a role-reversed Hero’s Journey tale, or is the taming of the shrew different from the taming of the dragon?

The issue here, purely from the point of view of drama, is one of difference. If, as Bruno suggests, the role of the man is to slay the dragon and the role of the woman is to tame the dragon that the man has become, then the difference between men and women, between their natures and gifts, clearly heightens the drama. Swapping the roles would suggest that the differences between the natures of their roles and gifts don’t amount to much, and indeed that the story could not only be role-reversed but recast with two men or two women and still be the same story.

Yet it seems clear to me that if the story can be recast in this way and still be the same story, that much of its drama has gone out of it. If it is in the nature of man to slay the dragon and, in doing so, to become the dragon, then the peril of the woman, who cannot become a dragon herself, is so much the greater in the act of taming. There is thus more drama in it at the basic level.

But I think it goes deeper than that. The reconciliation of opposites is at the heart of drama itself, at the heart of the tension that drives the drama. It is not merely the peril that each exposes themselves to in approaching the other (the man can lose his dragon fire; the woman can lose her life) but also the more profound and universal question of whether there is order or chaos in the difference of things. If two beings different in kind can be reconciled with each other fruitfully, this asserts order over chaos in the universe, which is the most fundamental dramatic question of them all.

But if all that is so, how can we also have the taming of the shrew trope, and how does it maintain the dramatic principle of difference? How is the man’s taming of the woman different from the woman’s taming of the man?

One thing that is constant between the two tropes is the imbalance of strength. In both cases, the man is more dangerous to the woman than the woman is to the man. The woman thus bears the peril in both forms of taming. The woman tames the dragon by daring to expose herself to his power. The man tames the shrew by showing her that she has nothing to fear from his power. The differnce between the two stories lies in which is the reluctant party and which makes the advance. But the advance of the woman to tame the dragon is different from the advance of the man to tame the shrew because the greater danger lies with the woman in each case.

A second imbalance lies in the woman’s fertility. Yes, biologically, it takes two to make a baby, as it does in the story world. But in stories, it is the woman who, so to speak, offers the gift of fertility to the man. The man can deal death. The woman can deal life. In stories, that is the essence of their difference, which is fundamental to the drama, and thus the taming of the dragon and the taming of the shrew are different stories. One cannot reverse the roles without switching to a different genre.

And so, returning to the Hero’s Journey, it would indeed seem that the trope belongs to men, for the man has gone out into the wild and has changed his nature to survive and triumph in the wild. He has slain the dragon and become the dragon and must, in turn, be tamed before he can return home.

In the fruitful union, the man provides the seed, but the woman provides the garden. Thus, while a man goes out and slays the dragon, the wild remains the wild, and the man becomes the dragon and must then be tamed. But if the woman goes out into the wild and tames the dragon, the wild is transformed and becomes a garden. None of this dynamic, none of this drama, can occur unless the man and the woman are different in kind.

Difference creates tension, but not just the tension that arises from conflict, which is really the least part of it. Difference creates tension through the need for resolution, for integration. The less difference there is, the less tension there is for resolution and integration. And the male/female difference is the one that creates the greatest tension and the greatest need for resolution and integration, and therefore it is not good for story to minimize the difference or to suggest that the roles are reversible.

But that is story. Story is not life. Truth, they say, is stranger than fiction. Is what is good for stories a good indication that it is also true in life? This gets to the question of whether the appeal of story is that it accords with and accentuates those things that we find in life itself, or if the appeal is that it gives us a fantasy of what we might wish life to be but isn’t?

Clearly, the answer to this is both. Stories can thump us between the eyes with the realization of what life is really like, or they can distract us from the dreary drudge of life as it really is. Which it is in this case, I leave as an exercise for the reader.

One or both of these refusals is often omitted from descriptions and diagrams of the Hero’s Journey, which betrays a fundamental misunderstanding. But that is a subject for another day.

Excellent points! But let’s explore a bit deeper this business of the dragon, which represents evil. In Revelation 12 we have St John’s vision of the woman and the dragon: “…Then the dragon stood before the woman about to give birth, to devour her child when she gave birth…Michael and his angels battled against the dragon….” It’s fair to say here that the woman is involved in a fight against the dragon that ultimately ends in hurling it into the lake of fire, certainly not taming it. So the woman participates in the fight, but not by wielding a sword herself but by giving birth to a son who will rule. Whatever you make of this, it’s clear that individualism doesn’t fit. (What do you make of it?)